Eye Books is a small, independent publisher championing extraordinary stories and overlooked voices since 1996. We publish bold fiction and non-fiction, work closely with our authors, and take pride in bringing unique books to adventurous readers.

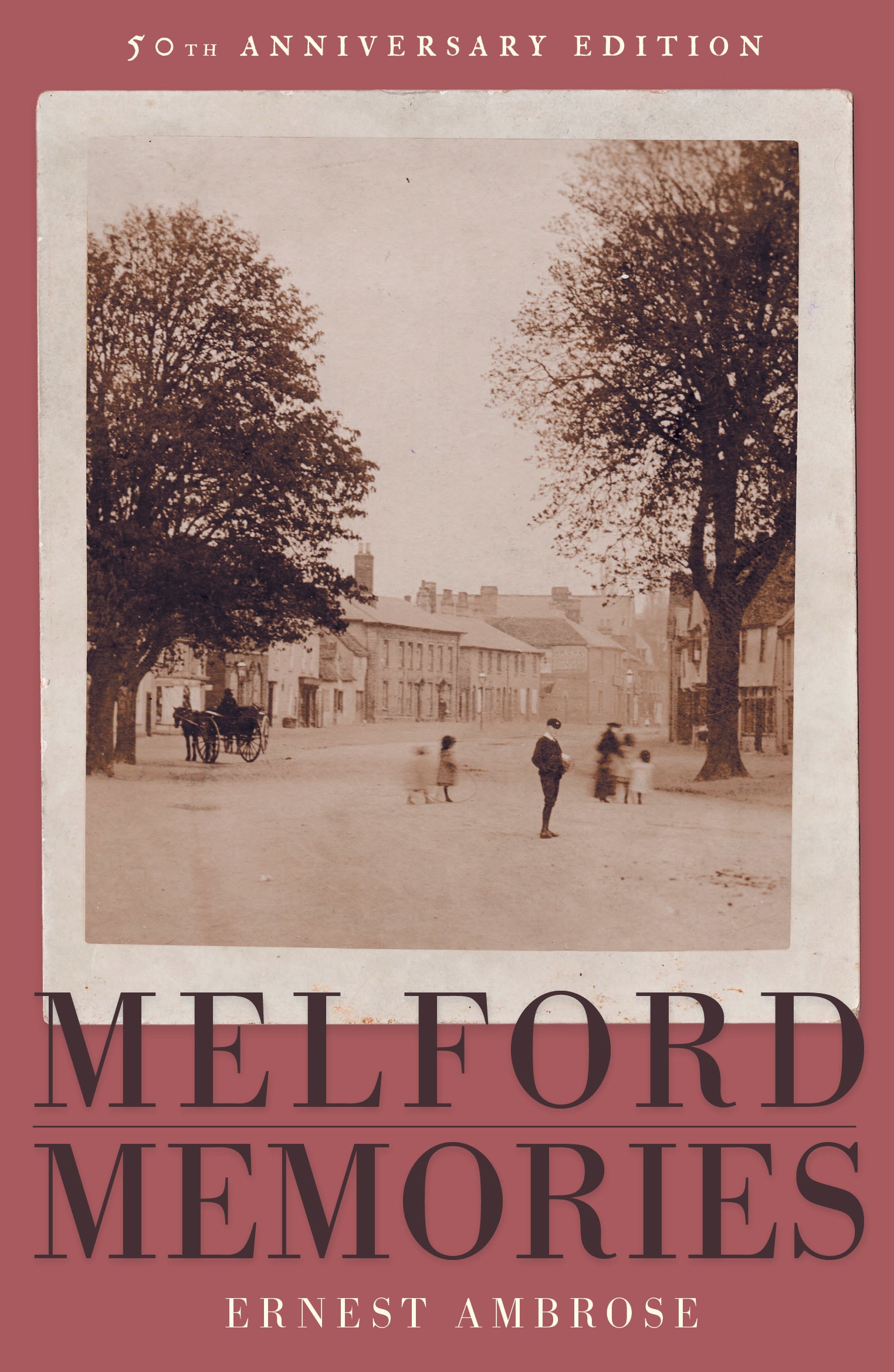

50th Anniversary Edition

‘Easily ranks alongside Lark Rise to Candleford’ Richard Morris

Born a stone’s throw from the church and educated at the village school, Ernest Ambrose was brought up to respect God, his parents, Long Melford’s two local squires and the rector.

That didn’t mean rural Suffolk life in the nineteenth century was quiet. Poaching was rife, the excesses of the Whitsun fair were an annual highlight, and young Ernie’s friends risked their necks to master the new-fangled ‘high bikes’, or penny farthings.

He witnessed the legendary street-battle when factory workers from neighbouring Glemsford stormed the village, the violence only quelled by a bayoneted militia. With the rest of his generation, he went off to the First World War. And, as the church organist in another nearby village, he heard at first hand the accounts of the hauntings that would make Borley Rectory a nationwide media sensation.

Looking back in his tenth decade, he describes a vanished world of rural customs and culture with wit, intelligence and a freshness of observation that have made Melford Memories – now reissued on the 50th anniversary of its first publication – a much-loved Suffolk classic.

‘Ernest was an intelligent and articulate man who witnessed nearly a century of change in the region. To anyone interested in our local history it is essential, if only because it’s such a damned entertaining read’ Andrew Clarke

‘Easily ranks alongside Lark Rise to Candleford’ Richard Morris, author of Foxearth Brew

‘This is absolutely wonderful. It’s quite gripping, it’s a got a really warm feel to it and it’s a fascinating read’ Sarah Lilley, BBC Radio Suffolk

UK postage is free if you spend £20 or more