Eye Books is a small, independent publisher championing extraordinary stories and overlooked voices since 1996. We publish bold fiction and non-fiction, work closely with our authors, and take pride in bringing unique books to adventurous readers.

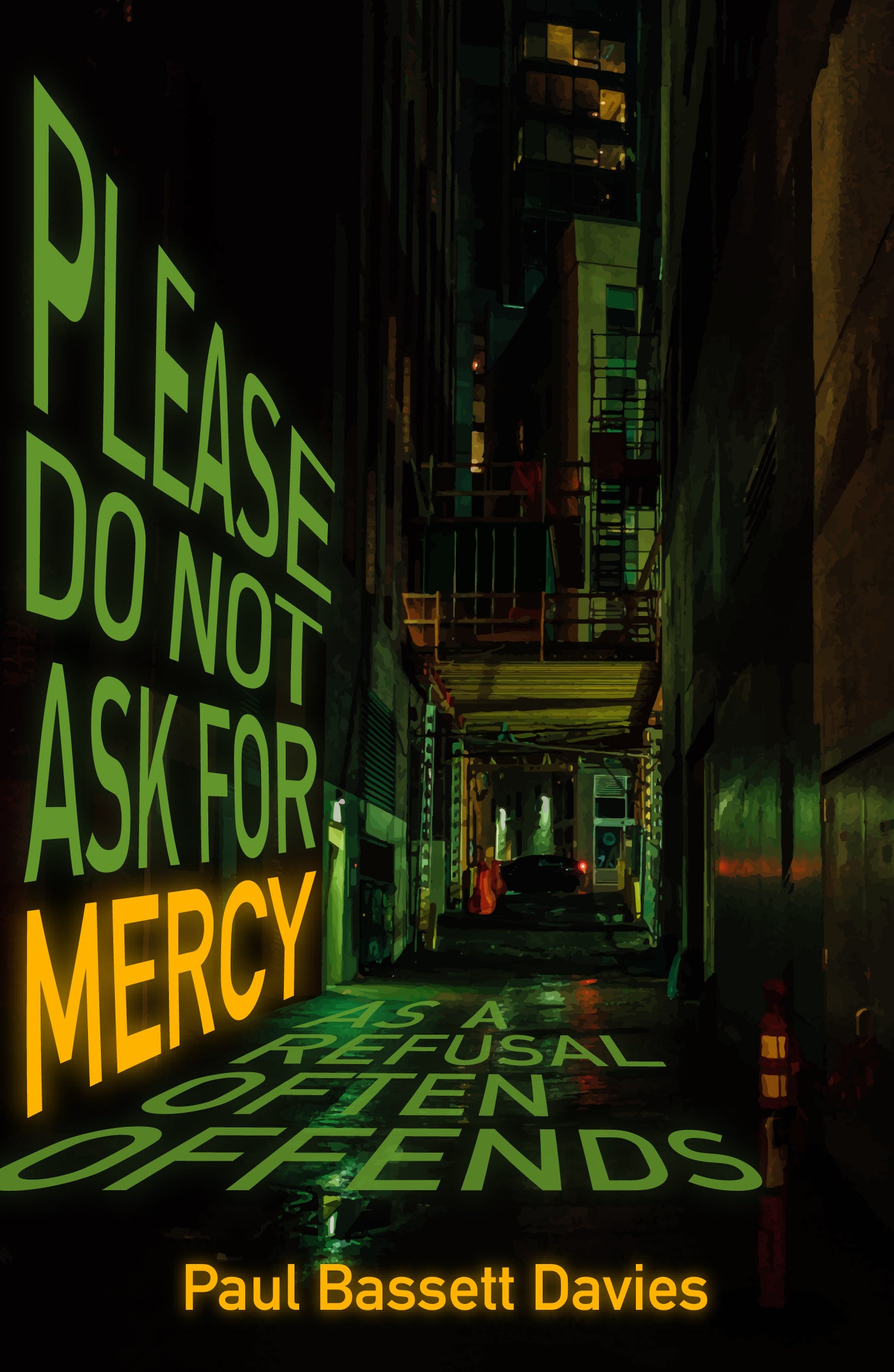

A darkly comic dystopian crime novel

‘Top marks for originality and subversive humour’ Maxim Jakubowski

Detective Kilroy is assigned to investigate a horrible murder. He’s a fine cop, from the brim of his hat to the soles of his brogues, but his inquiries, far from solving the mystery, lead him into a deeper one – and to Cynthia, an enigmatic woman with a secret that could overturn Kilroy’s entire world.

But where is this world? It seems both familiar and uncanny, with electric cars, but no digital devices, and the audience for a public execution arriving by tram. Meanwhile, the seas are retreating, and the Church exerts an iron grip on society – and history. Power belongs to those who control the narrative.

Kilroy is forced to take sides between the Kafkaesque state that pays his wages, and the truth-seekers striving to destroy it, all the while becoming increasingly besotted with a woman who may only love him for his mind – in an alarmingly literal way.

Please Do Not Ask for Mercy as a Refusal Often Offends is a dystopian satire that manages to be funny and frightening in equal measure.

‘Echoes of Douglas Adams at his more mischievous. Top marks for originality and subversive humour’ Maxim Jakubowski, Crime Time

‘A detective investigating a murder unwittingly pulls back the curtain on his dystopian world in this thrilling sci-fi mystery. Davies knows how to keep the pages flying’ Publishers Weekly

‘It questions power, propaganda and corruption, while maintaining emotional intelligence. It’s also bloody funny’ International Times

UK postage is free if you spend £20 or more